Original drawings by Trevor Pacelli Original drawings by Trevor Pacelli -by Trevor Pacelli The world of Pokémon has long been a favorite of both kids and adults on the autism spectrum, like me. I joined the Pokémon fandom at ten years old, my first game being Pokémon Ruby on the Gameboy Advance SP. Although I drifted away from the games once I hit adulthood, I still couldn’t help but keep up with the franchise. Eventually, I felt the urge to play the games again. In 2021, I bought a Nintendo Switch, and became the proud owner of four games: Pokémon Brilliant Diamond, Pokémon Legends Arceus, Pokémon Shield, and Pokémon Scarlet. While I admit the games’ quality is lackluster, and there are problems with disability friendliness, the chill environments of these Pokémon worlds with the diverse 1,000+ Pokémon delight me as much as when I was twelve. But unlike back then, I got sucked into a component of Pokémon that in turn sucked out what originally drew me to the franchise: competitive battles. Yes, a whole subculture of Pokémon fans is all about competitive battles. I tried entering the scene for something "fun" to do and quickly found I could not do so using my favorite Pokémon. I did a lot of research on how to build the right team and build them in-game (which always took forever). I spent every day on an online battle simulator (Showdown!) to test out teams I made, learning through trial and error why my strategies weren’t working. Whenever I thought I found a good team, losing enough times made me realize the team's blind spots, requiring building a new team from scratch. I was thrown into many gamer-rage fits from the constant losses, which affected my general happiness throughout the day. In addition, the sweat, blood, and tears shed from my practice never helped me win. But for quite a while, I thought I was improving. So, I took a three-day trip to Portland for a Pokémon video game championship. I wasn’t comfortable enough to be in the official tournament, but I went as a spectator who partook in battles on the side. The trip started off with a minor car accident that caused quite a bit of stress for me, and it didn’t get much better from there. On day one at the Portland Convention Center, I did only one battle, which I lost easily. On day two, the official competitive battles I could watch were few and far between, with most of my time spent waiting until the next battle to either watch or partake in. I had one win, but then four straight hard losses. By that final loss, I had had enough. I didn’t go back to the convention center, but did some tourist things around Portland that evening and the next day before going home. So, overall, my tournament experience was much less than I had hoped for. Portland set the first ripple of an important lesson I had to learn: Sometimes, you must accept that no matter how hard you practice, you will never be good at a certain hobby. That’s exactly what I’m finding with my incapacity to stand a chance against other players. Even if I think I know the strategy of whomever I’m playing against, he throws a curveball at me, and I don’t have the mental processing speed to readjust my plan under pressure. So, I have learned that it’s best to give up on Pokémon battles and stick to the hobbies I enjoy and others have told me I’m good at, like cooking, photography, story writing, and drawing. The last of these is why I became a Pokémon fan in the first place. Because I love the fun Pokémon designs, it inspired me to draw my own Pokémon creations over the years, which can be seen on my Instagram page, @Murro_Region. This is something I believe I should stick with since it gives me a sense of self-accomplishment. This isn’t the first time I gave up a hobby. Here’s my blog post about when I decided to stop writing weekly movie reviews. To decide whether it’s time for you to give up a hobby, ask yourself:

Trevor Pacelli is an adult author and illustrator on the autism spectrum. Trevor’s Books | Trevor’s Instagram @Murro_Region

0 Comments

By Trevor Pacelli In thinking back to my childhood, I don’t recall knowing of any blind people at school or anywhere else; my only exposures to the blind community are limited to three media properties: The first is a blind girl named Marina from the hit TV series Arthur, who made a couple of appearances as the friend of a character named Prunella. One of those episodes taught kids the dos and don’ts of treating friends with disabilities, such as not trying to be too helpful unless they specifically ask for help. The second is from Pokémon: Ruby Version; in this game, there were three ultra-rare Pokémon, Regirock, Regice, and Registeel, who needed to be obtained by decoding a series of puzzles with braille descriptions. Being the Pokémon geek I was back in sixth grade, I was so desperate to get to these three legendary beasts that I made my mom drive me to the library to check out a book on translating braille… only to find out the dictionary we had at home already had a braille translator! Whoops! The last is Toph, the blind earthbender from Avatar: The Last Airbender. She used earthbending (or moving rock and dust with her mind) to create a mental picture of her surroundings by using the ground’s vibrations felt through her bare feet. Back then, I didn’t care much about her, mostly because I was a dweeby tween who believed her blindness made her incomplete. Later as an adult, I rewatched the whole series on Netflix, and Toph essentially became my favorite character, not just because of her rough n’ tough personality, but also because of how she turned her disability into an advantage to become “the most powerful earthbender in the world.” Ultimately, I was a pretty privileged kid back then who wasn’t able to consider the struggles of the blind community, which was much different from what I’ve learned in my research for this book. For instance, I discovered that when seeking out accommodations, blind people often lack authority when requesting accommodations from schools and workforces. Among those blind people raised by sighted parents, it’s common for their parents to think little of what their supposedly handicapped child can accomplish, in turn depriving them of fruitful experiences. Read more about the portrayal of blindness in film and media in my book, What Movies Can Teach Us About Disabilities. --by Trevor Pacelli, author of What Movies Can Teach Us About Disabilities

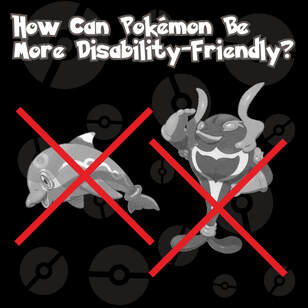

Autistic people have all sorts of special interests, some are temporary, and others are lifelong. Some even are drawn to a common special interest. Pokémon in particular has quite a bit of appeal to people with autism because the games are run by a simple set of predictable rules that have remained mostly static over many years. It’s a nice blanket of familiarity as someone with autism goes through a long life full of constant change. Every three years, a new generation of Pokémon is always expected to begin, meaning a new set of games debuts with around a hundred brand new Pokémon added to the series. Each game follows a rather similar pattern: you start your adventure after choosing between one of three starter Pokémon, one a grass type, one a fire type, and one a water type, to be your first companion. You explore the region. You battle eight gyms. You take down an evil team. A rival often intrudes your way. Once you win all the badges, you take on the Elite Four and the champion to beat the game. While playing this game, the type matchups resemble a big complex system of rock-paper-scissors following a logic-based system: grass is strong against water, fire is strong against grass, water is strong against fire, and so on. Because many autistic people love numbers and statistics, and because the adorable Pokémon of this franchise are all so vibrantly colorful, researching the stats and type matchups of these lovable creatures offers a lot of comfort for ASD in a sensory-heavy world. It all seems fine and dandy… until the latest games, Pokémon Scarlet and Pokémon Violet, introduced a new Pokémon that reminded the fanbase of a problem that has plagued the entire series since day one that has been particularly troublesome for the ASD community. This Pokémon is Finizen, a cute little blue dolphin whose evolution, Palafin, still looks the same besides a pink heart appearing on its chest. While this Pokémon’s stats start off rather mediocre, Palafin contains a special battle gimmick: When sent out into battle and then called back to the trainer’s party, the dolphin ‘mon changes into its “hero” form, with a Superman aesthetic and insane battle stats rivaling most legendary Pokémon, plus a scary attack stat of 160 (the series’ highest attack stat is 190). What makes these Pokémon even more adorable is that Finizen evolves into Palafin at level 38, a nod to the year 1938, when Superman had his first comic book appearance. Unlike most Pokémon who evolve naturally at a certain level, Finizen only evolves when it levels up to at least level 38 while battling in multiplayer, a feature unique to Scarlet and Violet where up to four friends can connect over Wi-Fi and explore the game together. What could possibly be so bad about this though? Who wouldn’t want a pal like Palafin in Paldea, who evolves while playing with some pals? Well, there are lots of game players, especially those with developmental disabilities, who already struggle to make friends, meaning unless they own a Discord or get lucky enough to encounter a Palafin inside the "tera raid dens" throughout the game, they’ll never get to register Palafin into their Pokédex, and thus will never get to fulfill the series’ slogan of, “gotta catch ‘em all!” This can be true for lots of people who may be socially anxious, not have many friends, or may not have other friends who also play the games, but it’s more especially true for people with developmental disorders, including autism, who already struggle to make friends. This problem isn’t unique to just Palafin, nor is it unique to Scarlet and Violet, way back at the start of the franchise, right from the Red and Blue days, some Pokémon were made to be only obtainable by hooking up link cables into the Gameboy and trading Pokémon amongst friends. The major releases always have two versions for this specific purpose; Oddish could be caught in Blue version but not Red, and Vulpix could be caught in Red version but not Blue. To add to that toilsome grind, some Pokémon, such as Machoke, Kadabra, and Graveler, could only evolve by trading. Bottom line, nobody could ever complete the Pokédex of any of these games without having friends to trade with. With the whole “gotta catch ‘em all” message that was pressed in the franchise’s early years, it seemed to punish players who didn’t have friends. This is why the game Pokémon Legends: Arceus was revolutionary for the series… since the players at last no longer needed others to complete the Pokédex. Kadabra, Machoke, and Haunter now evolved simply by being given a new in-game object called a "link cable," and version-exclusive Pokémon were gone; all Pokémon in the Pokédex were available in the same game cartridge. Yet even without the need for this game, the past few generations have made trade-exclusive evolutions, such as Gengar, Machamp, and Dusknoir, available to find in the wild. Thus, it was easier for a player to battle with that one powerful Pokémon on his team as well as fill the dex up. But version-exclusive Pokémon didn’t go away in the major games that came in two versions, especially not in Scarlet and Violet. So in the span of a year, with the existence of Palafin, GameFreak took one step forward and two steps backward. In future games, the online "trade" component of the games really should be exploited further to make completing the dex easier for people who may struggle to make friends for any number of reasons. I propose that it should be made possible for someone to make a request online for a specific Pokémon they want, and some other player online at some other time could fulfill that request by trading with that person that specific Pokémon they need. As for Palafin, its evolution method just needs to change. It’s uncertain whether the "multiplayer" feature from Scarlet and Violet will be around in future mainline Pokémon games, so Finizen needs a simpler evolution method, such as by maxing out its happiness with its trainer. If it’s been done before with Feebas’ evolution into Milotic, or Eevee’s evolution into Leafeon, Glaceon, and Sylveon, then surely changing a Pokémon’s method of evolution can be done for Finizen as well. There are other ways Pokémon isn’t disability-welcoming, starting with its treatment of shiny Pokémon. Each Pokémon has a "shiny" variant with a different color palette, averaging at a 0.01220703125% encounter rate, and many serious players regularly commit dozens of hours to obtain just one shiny of a particular Pokémon. Pokémon Legends: Arceus had a revolutionary new feature in its programming that made shiny hunting infinitely easier; not only do they now appear in the overworld as opposed to exclusively in battle, but a little chime sound effect also goes off with these little stars that glitter around the Pokémon, indicating right away that it’s a shiny. However, Pokémon Scarlet and Violet left out the stars and sound effect; although the shinies still appeared in the overworld, shiny hunting was still much harder than in Legends: Arceus. Most Pokémon’s shinies can be noticed pretty easily, such as Lechonk’s shiny being bright pink instead of its usual black and brown, but others’ colorations are so minuscule that even one with great eyesight couldn’t tell them apart unless they were paying very close attention, like Paldean Tauros’ shiny being just two slightly different shades of black from its original. It may sound like no big deal, but what if a colorblind player wanted to shiny hunt? They wouldn’t be able to benefit from the sound effect to let them know a shiny was nearby. Or what if somebody had hearing problems? They wouldn’t be able to benefit from the little stars that appear. On the note of these mainline console games feeling like steps backward from the game before it, many fans have for years complained that it’s time for the games to put in voice acting. They say it’s awkward to watch the lifeless character models move their lips silently while they’re forced to read the text on the screen to know what they’re saying, and with the series now on the Nintendo Switch, they are without excuse to still not have voice acting in their games. Although it’s understandable why the games still lack voices (it’s expensive, and would not fit with when the NPCs talk to the main character… who has a customized name). Although, the games could still benefit from voice actors, which would help blind and dyslexic game players. One last way Pokémon isn’t entirely accessible for people with disabilities is in Pokémon Go. Wheelchair users have reportedly struggled to access numerous areas the mobile game made them go to, and the act of carrying a phone around while playing proved difficult for players with physical disorders such as motor impairment. Gladly, the COVID-19 pandemic forced the game’s developers to include more stops that also happened to be more accessible for people who maybe couldn’t leave their homes because of physical disabilities. These types of issues about accessibility in Pokémon, and other video games in general, really need to be made more apparent, because there’s a valuable symbiotic relationship between people with disabilities and this long-lasting series. BBC even did a story on an anxiety-stricken autistic teenager who spent five years refusing to leave his house, and Pokémon Go finally persuaded him to step outside. Stories like this are why I’d like to see more community meetups for people who play the main Pokémon games, and not just for the trading card game or for Pokémon Go. I went to one this past year that was a part of PAX West 2022, and it was an awesome time for me to meet others with the same interest as me, others I could trade and battle with in person. But I want to see something more regular than that happen in my own community, something that can easily help more people like me form friendships over a common interest. I was one of those kids who didn’t naturally value friendships up until high school and only ever invited another kid over to my house to trade Pokémon with about three times, so having something like a regular Pokémon club would have helped me immensely in not only making friends but learning about the value of friendships. --Trevor's Books | Trevor's Murro Region Pokemon Instagram Page |

Inspiration for Life with AutismThis blog has a variety of articles about people living life with autism, and topics and ideas that can help in the journey. Guest bloggers are welcome. Inspired by Trevor, a young adult film critic, photographer and college graduate on the autism spectrum. Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed